I have argued, controversially to some on the left, that it is important to grapple with ideas on their own terms before merely analyzing their motivations. American conservatism is historically intertwined with white racism in such a way that nearly any conservative idea could plausibly be understood as an appeal to racism, but most of those ideas can be expressed and justified in non-racial terms, and deserve to be taken at face value. The trouble with Giuliani’s comments is that they lack the coherence necessary to be analyzed as an idea. Brush away the bilious rage he has emitted, and nothing solid remains behind.

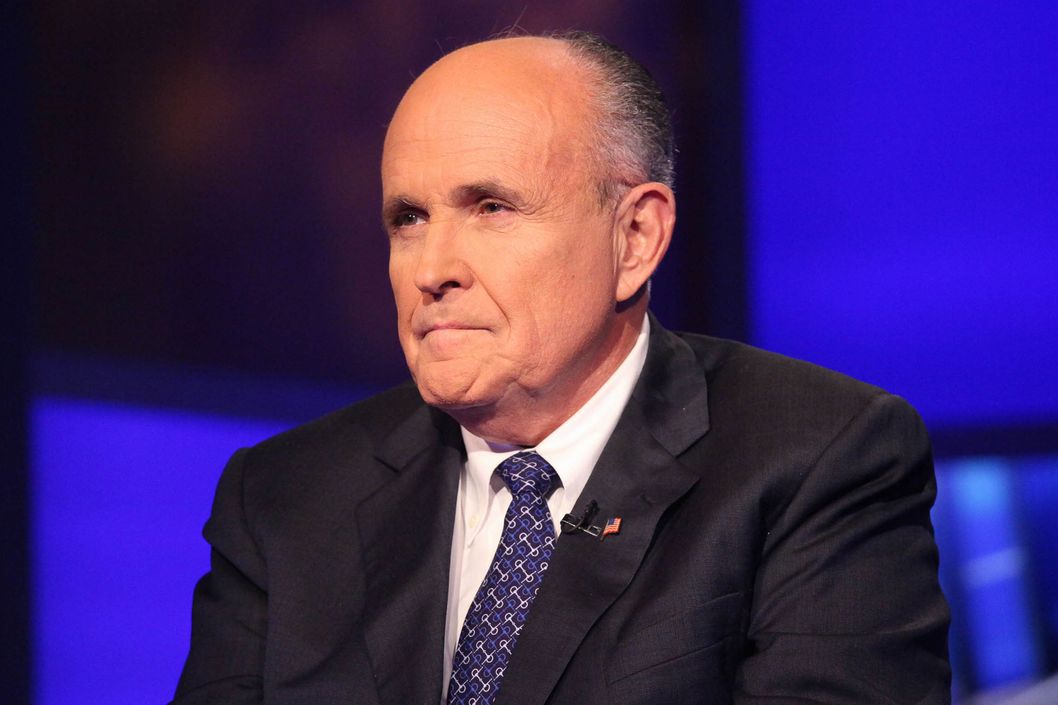

The original basis for Giuliani’s comments was Obama’s allegedly unusual upbringing. “He wasn’t brought up the way you were brought up and I was brought up, through love of this country,” alleged the former mayor. As Wayne Barrett points out, Giuliani’s father was a mob enforcer, and he and his five brothers all avoided military service during World War II. What about this upbringing in any way suggests it conveyed some deeper patriotism than Obama’s?

Giuliani subsequently clarified his original remarks, though not in the way he intended, by asserting that Obama’s alleged anti-Americanism amounted to “socialism or possibly anti-colonialism.” Here Giuliani is reprising the theories of Dinesh D’Souza, who has described Obama as fundamentally influenced by Kenyan anti-colonialism. Unfortunately for Giuliani, D’Souza’s racism is so transparent not even many conservatives care to defend it any longer.

Giuliani also explained that Obama’s anti-Americanism comes through in his selective use of press conferences:

“He sees Christians slaughtered [in Egypt] and doesn’t stand up and hold a press conference, although he holds a press conference for the situation in Ferguson,” he said. “He sees Jews being killed for anti-Semitic reasons, doesn’t stand up and hold a press conference. This is an American president I’ve never seen before.”Of course, the more obvious explanation for why Obama held a press conference to address Ferguson but not Egypt is that Ferguson is located in the United States of America while Egypt is not. For a president to deliver a speech urging calm, while expressing sympathy with underlying grievances, is a completely standard act for an American president. (George Bush did it in Los Angeles.) Had Obama declined to speak about Ferguson, he could have just as easily been accused of indifference to the lives of Americans.

National Review’s Kevin Williamson attempts to rescue Giuliani’s smear by shearing off its ugly insinuations, and boiling it down to a simple left-versus-right debate about American goodness:

For the progressive, there is very little to love about the United States. Washington, Jefferson, Madison? A bunch of rotten slaveholders, hypocrites, and cowards even when their hearts were in the right places. The Declaration of Independence? A manifesto for the propertied classes. The Constitution? An artifact of sexism and white supremacy. The sacrifices in the great wars of the 20th century? Feeding the poor and the disenfranchised into the meat-grinder of imperialism. The gifts of Carnegie, Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Morgan, Astor? Blood money from self-aggrandizing robber barons.It is certainly true that there is a strain of left-wing thought that implicitly or explicitly rejects patriotism, and which deems the United States no better than, or perhaps even worse than, other countries. The trouble is that Obama has explicitly and repeatedly rejected this thinking. Even Obama’s endlessly criticized 2009 press conference, in which he gave an answer on American exceptionalism that conservatives deemed insufficiently flag-wavey, ended on an affirmation of American exceptionalism (“I think that we have a core set of values that are enshrined in our Constitution, in our body of law, in our democratic practices, in our belief in free speech and equality, that, though imperfect, are exceptional”).

The liberal conception of American exceptionalism espoused by Obama, while different than the left-wing conception with which Williamson conflates it, is also different than the conservative version. The left rejects American exceptionalism. The right treats it as something inherent in the American character, rather than, as liberals see it, an ideal that must be struggled toward and has often been failed. Obama’s treatment of the issue lies firmly in liberalism, rather than the left.

And of course the key element of Giuliani’s charge is that Obama has broken completely from the liberal tradition. He does not accuse Obama of being a weak-spined liberal like Jimmy Carter. He calls Obama worse than Carter:

What country has left so many young men and women dead abroad to save other countries without taking land? This is not the colonial empire that somehow he has in his hand. I’ve never felt that from him. I felt that from [George] W. [Bush]. I felt that from [Bill] Clinton. I felt that from every American president, including ones I disagreed with, including [Jimmy] Carter. I don’t feel that from President ObamaJamelle Bouie, with excessive generosity, concedes that (smear aside) Giuliani is onto something. “Compared with the visions of his predecessors,” writes Bouie, “[Obama’s] is less triumphant and informed by a kind of civic humility.”

In fact, previous Democratic presidents have also acknowledged American historical failures, in language every bit as frank as Obama’s. In a famous 1977 speech, Carter conceded, “For too many years, we’ve been willing to adopt the flawed and erroneous principles and tactics of our adversaries, sometimes abandoning our own values for theirs.” Clinton mournfully acknowledged American slavery and support for military dictatorships in Guatemala and Greece. Obama has kept fully within the liberal tradition of conceding America’s inconsistent history of upholding its ideals without abandoning the ideals themselves.

Any attempt to salvage an idea from Giuliani’s gaseous smear invariably fails. His dark insinuation that this liberal Democratic president hates America in a way unlike other Democratic presidents is under-girded by nothing but a generalized suspicion neither he nor his supporters can define.

largely forgotten man sought attention on Wednesday night before returning to obscurity on Thursday, according to reports.

largely forgotten man sought attention on Wednesday night before returning to obscurity on Thursday, according to reports.

udy Giuliani is giving me Soviet flashbacks.

udy Giuliani is giving me Soviet flashbacks.

The photos are nightmare producing.

Later edit:Sorry, I didn't look at the photo. Wish there was a way to delete comments.

Inasmuch as money is the "free-est" and most effective resource in seeking public office, correlation of pre- and post- election contributors and investors could be enlightening ... if voters were aware and inclined and capable of considering factual information in selecting their "leaders"... Scalia, Thomas, Roberts and Alito notwithstanding.

Giuliani continues to provide the entertainment divisions of mass media enterprises with the spice of 'stupidity' with which to stir, antagonize and misdirect the public away from thought and knowledge.

I Laufhed so hard I hurt -

I couldn't place the face -

But I kept reading --- going along w/ the spirit of it so to speak ---

--- Oh My Gawd ANDY --

You set me up good - !!! -

I really did know the face, but I couldn't put a name --

And I'm trying hard - ANDY -!

And then I start reading the comments -

And Andy " OMFG " -

--- It ! - IT! - ITS!!!---

--- rudy --

rudy ???

YES !! RUDY! --

rudy -g- ???

"WE GOT U RUDY "

We were quoted to say --

THANK YOU RSN & THANK YOU ANDY --

I Owe U --- 99%OU ---

I needed that laugh although it nearly killed me --

Oh yeah and thank you Rudy ---

what does the G stand for ---???

" I forgot "

RSS feed for comments to this post